Like this post? Help us by sharing it!

On the 11th of March 2016, Japan will be marking five years since its ‘triple disaster’: the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown that collectively claimed over 18,000 lives in 2011.

To mark the anniversary of the disaster, this month at Inside Japan Tours is going to be all about Tohoku: not just remembering the disaster and its aftermath, but celebrating the many delights of this little-known and underrated region. We’ll be posting a series of six blogs over the course of the month, including first-person experiences of the disaster, accounts of the subsequent recovery efforts, and our impressions of Tohoku five years later. This week, we’ll be taking stock of the disaster itself: what actually happened, who it affected, and how it was experienced by the people who were there.

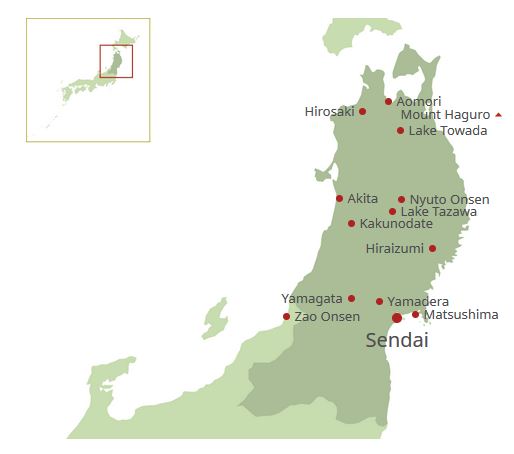

Where is Tohoku?

Tohoku is the northernmost portion of Japan’s main island, Honshu. Despite its many charms – including beautiful Matsushima Bay, the ancient temples of Hiraizumi, rugged Shirakami-Sanchi National Park and the well-preserved samurai town of Kakunodate, Tohoku has always been one of the least visited of Japan’s regions – even more so since the earthquake.

What happened?

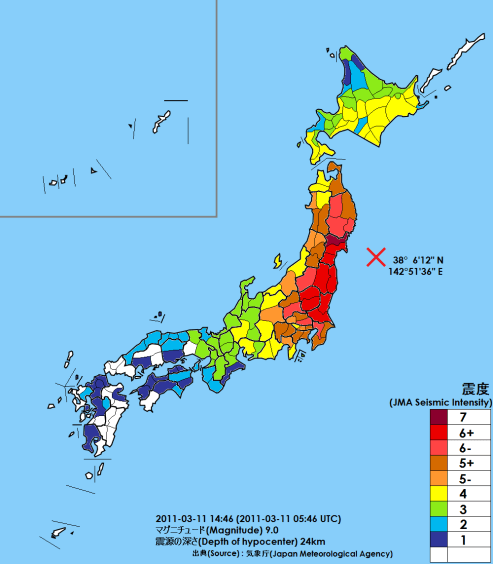

The earthquake

The earthquake’s epicentre was located 70 kilometres east of the coast of Tohoku, and at a magnitude of 9.0 it was largest earthquake ever to hit Japan (and the fourth-largest earthquake in earth’s recorded history). The earthquake was so huge, in fact, that it moved Japan’s entire main island 2.4 metres to the east, and shifted the earth on its axis by 10-25cm. It literally rocked the world.

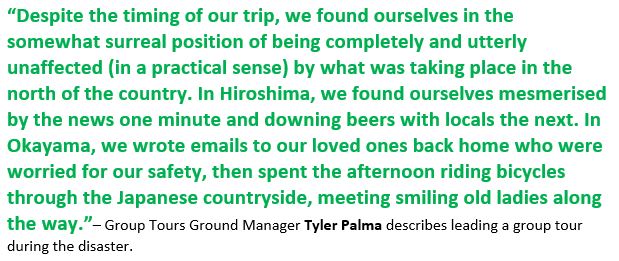

Despite the many mind-boggling statistics associated with it and the large area affected, the earthquake itself was only responsible for about 7.5% of the disaster’s casualties. Japan is extremely well geared-up for earthquakes, and buildings are built to withstand this kind of event. Though some shaking was felt as far away as Kyoto, the rumblings there were minimal enough that our Group Tours Ground Manager Tyler was assuring everyone that it was probably a passing bullet train.

In the capital the shaking was considerable – enough to give anyone in a skyscraper a really good scare, and for the subways and train lines to be closed for the rest of the day – but it was nothing compared to what was experienced in Sendai, the closest city to the epicentre. There was little sense of panic, no buildings collapsed, and in its aftermath people largely continued about their day-to-day business. Most people were not aware of the extent of the devastation in Tohoku until hours later.

On March 17, nearly a week after the disaster, the BBC reported that “parts of Tokyo… are beginning to resemble a ghost town”, but in reality the city was largely unaffected. Tyler, who by then was in Tokyo with his tour group, noted that things seemed a little more subdued than usual – but reports of mass exodus and bare supermarket shelves were hugely overstated in the foreign media. As tour leader Tom Orsman assured us, “there is certainly no food shortage or even a hint of one. I would be the first to leave if there was”.

The tsunami

Compared to the earthquake, the reach of the ensuing tsunami seems at first glance much smaller: it affected a section of coastline around 670 kilometres long, travelled as far as 10 kilometres inland, and inundated a total area of around 560 square kilometres – about a third of the size of Greater London.

But while its effects may have been localised, the devastation within these areas was almost total, accounting for around 92.5% of the disaster’s final death toll. Entire towns were swept away by waves up to 40 metres high, leaving nothing but square foundations where once had been buildings. Cars and boats were picked up and scattered across roads and fields, fishing equipment was deposited on clifftops, existing surge defences were destroyed, and over 100 tsunami evacuation sites overwhelmed. Towns such as Minamisanriku and Ishinomaki were wiped from the map as though with the sweep of a broom.

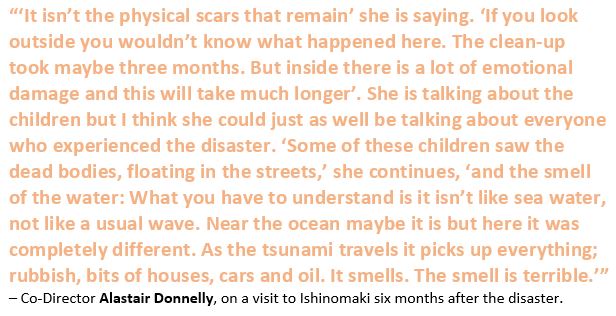

It was in these areas that the impact of the disaster was most acute. Inside Japan’s Co-Director Alastair recalls hearing the testimony of a preschool teacher who survived the tsunami in Ishinomaki:

Read more from Alastair here.

Read more from Alastair here.

The nuclear emergency

After the initial shock of the earthquake and tsunami, the nuclear emergency at Fukushima Daiichi was what claimed the lion’s share of the headlines across the globe. The meltdown may have claimed no lives directly, but its potential implications seized the world’s collective imagination.

In reality, the nuclear exclusion zone (a 30-kilometre radius surrounding the Fukushima power plant) was tiny, and absolutely miles from anywhere tourists were likely to visit. As tour leader Tom Orsman reported from Aizu Wakamatsu just a few months after the disaster, radiation levels just 100 kilometres from the plant were “less than in Rome, similar to Hong Kong, and not significantly higher than in London” (read more here). Most of Fukushima Prefecture was, and is, completely safe.

Later in the month, I’ll be looking into the nuclear disaster and its effects in more detail, and hopefully putting some of the fallout fears to bed. Please do watch this space.

The economic fallout

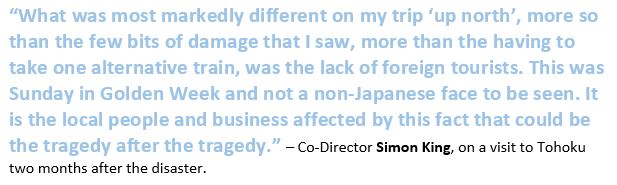

The earthquake, tsunami and nuclear emergency are often referred to as Japan’s ‘triple disaster’, but in fact there was a fourth disaster whose effects were felt throughout Japan – not just in Tohoku. As Inside Japan Co-Director Simon noted on a visit to the north just two months after the disaster:

This drop in visitor numbers was not limited to Tohoku. Thanks to the sensationalist (and occasionally vastly erroneous) reporting in the foreign media, most of the world was under the impression that Japan as a whole was a no-go zone. The French media channel TF1 reported, for instance, that “railways and highways throughout almost the whole Japanese archipelago were closed”, while KBS in Korea claimed that Tokyo’s Narita Airport had been flooded – both patently untrue (source). Misled by the media and ill-informed FCO advice, many Inside Japan Tours customers understandably cancelled or postponed their trips in 2011, and our staff made personal sacrifices in terms of hours and pay to ensure the company would weather the storm.

And if we were feeling the squeeze, the consequences for business owners in Japan were even worse. The spring immediately following the disaster, JNTO reported that visitor numbers to Japan were just a quarter of what had been expected, even though most areas of the country were untouched. Those of our customers who did decide to continue with their trips experienced little or no disruption, and found that the Japanese people they met were extremely grateful that they had not cancelled their visits.

Thankfully, Japan is now experiencing record numbers of visitors – so many, in fact, that our tours now sell out months in advance. Economic respite has come more slowly to Tohoku, however, where the spectre of nuclear fallout still looms in the minds of many. Here, the economic effects of the disaster are still being felt.

Next week I’ll be covering the aftermath of the tsunami and the ensuing recovery efforts, so stay tuned!

If you would like to lend your help to those still affected by the earthquake and tsunami, we are currently raising money for Second Harvest Japan, a charity that continues to provide food and support to survivors. Amongst other fundraising activities, 12 of us will be running the Bath Half Marathon next Sunday! Click here to support us.