Like this post? Help us by sharing it!

In this blog post, InsideJapan tour leader Mark Fujishige extols the virtues of the humble onigiri: the Japanese rice ball.

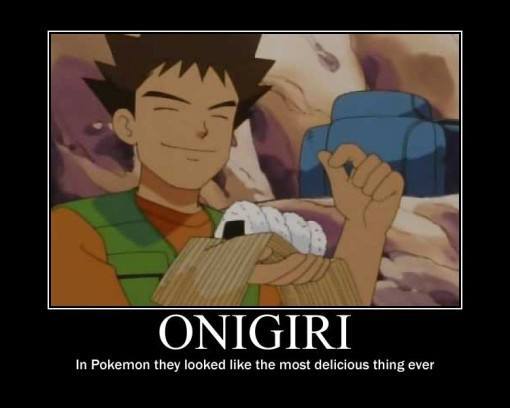

A staple of any healthy anime- or manga-based diet should include a triangular-shaped object made of rice, with or without seaweed and/or filling. This would be the beloved onigiri. While you can’t believe everything you see on television, this is something you can file under the “truth!” category with confidence. The onigiri does indeed hold place of pride on the Japanese table and in the heart.

I won’t be telling you how to make onigiri or extolling its culinary virtues and possibilities (I’ll save that for another day). I want to look a little closer at what I consider one of the best food-related Japanese inventions ever: the packaging.

It’s generally believed that rice, as so many other things, came to Japan from continental Asia via the Korean peninsula. Fossilized rice plants found in Okayama Prefecture indicate the possibility that it has been in Japan for 6,000 years. That’s definitely enough time for it to become established as a pillar of the Japanese diet. In fact, it was so valuable that at one time, it was even used as currency.

In a similar way, nori, dried sheets of seaweed, also reached Japan via the Korean peninsula, and happened a bit more recently; think late 16th century. However, the value that nori holds is one of nutrition. Packed with vitamins, nutrients, and enough iodine to keep your hair black for decades (according to my grandmother), seaweed has been an integral part of the Japanese diet for centuries.

Now, fast-forward about a hundred years to late 17th century, around the middle of the Edo Period (1603 – 1868), and you’ll find the onigiri in a form that we’re familiar with today: nori wrapped around rice. The nori keeps your fingers free of the sticky rice, the rice keeps you full, and the format is a prime example of on-the-go sustenance.

Moving on to the more recent past: the 1970s. Here we find changing tastes and trends, and the preferred style of onigiri is one with crisp nori. It’s easy to imagine how a dry sheet of seaweed wrapped around a moist ball of rice would turn soft and pliable in a matter of minutes, but not quite so easy to imagine a way of keeping the nori as crisp as possible for as long as possible, with mess and hassle kept to virtually nil.

Fast-forward one more time, just a few years, to the end of that decade. Here we find, “M-san,” who worked at a shop selling prepared food in the city of Iida, Nagano Prefecture. This is the brilliant mind that first developed the cellophane packaging system that would keep the moist rice and dry nori separate until moments before consumption. Enter an entrepreneurial wholesale dealer, and the rest is culinary and cultural history. These days, you can even purchase nori encased in the cellophane wrappers, so you can make your onigiri at home, but still enjoy crisp nori. May wonders never cease!

At the Miraikan in Tokyo, you can marvel at and interact with some of the latest developments in science and technology that are shaping our futures. However, at the nearest 7-11, you can experience an invention of a different greatness. One that, I think, enriches our culinary lives in no small way.

Below you’ll find a video demonstrating the “correct” way to utilize this food technology, and unwrap the little bundle of joy.

Itadakimasu! (Let’s eat!)

Video: Anna Fujishige