Like this post? Help us by sharing it!

When reading Matt’s blog post on itasha car culture, I was struck by an awful thought – we have never explained to you what an otaku is. We’re constantly referring to them, referencing their culture and generally bandying about the term – yet we’ve never once written a post explaining this important part of modern Japanese culture to you, our loyal readers. I can only apologise, and attempt to redress this deficiency now.

What is an otaku?

Otaku is usually translated in English as “nerd” or “geek”. Wikipedia, that font of all knowledge, defines otaku as those “with obsessive interests, commonly the anime and manga fandom.” This is indeed the case, but the idea goes much further than this cursory definition suggests.

To understand the world of otaku, you have to understand the world of manga and anime – a world that’s much deeper and more complex than most Western adults appreciate. In the West, cartoons and comics have traditionally been the preserve of young children and stereotypically nerdy adult males; in Japan they are consumed and enjoyed by everyone from teenage girls to besuited businessmen. There is no shame in being seen reading a manga comic book on your daily commute to work, and every convenience store has a large collection of comics on display – never without a few readers loitering beside them, their noses buried in the pages of the latest serialisation. The upshot is that in Japan, manga (and anime to a lesser degree) is taken seriously in a way that it just isn’t in the West.

Otaku are most commonly associated with manga, but there are otaku in various other fields too. In fact, the Nomura Research Institute (which has made two major studies into the subject) has identified 12 essential types of otaku: manga, pop idol, travel, PC, video game, automobile, anime, mobile IT equipment, audio-visual equipment, camera, fashion, and railway otaku. Phew. To delve into all the available permutations and subdivisions would be a mammoth undertaking and well beyond the scope of this post – so it must suffice, for now, to know that there are many kinds of otaku. A great many indeed.

All of these otaku share a set of defining characteristics – but as we’ll come to see, what these characteristics consist of is largely a matter of perception. What defines an otaku is up for debate.

The origins of otaku

The term otaku first appeared in a 1983 essay by columnist and editor Akio Nakamori (real name Ansaku Shibahara) in the manga magazine Manga Burikko. I won’t go into it in too much detail (and trust me, you wouldn’t want me to) but the magazine existed between 1982 and 1985, and published various kinds of manga – much of it pornographic.

Nakamori’s short, vituperative essay, entitled “This City is Full of Otaku”(街には『おたく』がいっぱい), paints a thoroughly negative portrait of the otaku subculture based on his observations at Comiket, a Tokyo convention for selling self-published material (of which more later):

“How can I put this? They’re like those kids — every class has one — who never got enough exercise, who spent recess holed up in the classroom, lurking in the shadows obsessing over a shogi [Japanese chess] board or whatever. That’s them. Rumpled long hair parted on one side, or a classic kiddie bowl-cut look. Smartly clad in shirts and slacks their mothers bought off the ‘all ¥980/1980’ rack at Ito Yokado or Seiyu [discount retailers], their feet shod in knock-offs of the ‘R’-branded Regal sneakers that were popular several seasons ago, their shoulder bags bulging and sagging — you know them.”

He goes on to expand his definition from manga nerds to include various other social outcasts – trainspotters, sci-fi fanatics, those who idolise pop stars – and rounds off his essay with the pronouncement:

“These people are normally called ‘maniacs’ or ‘fanatics,’ or at best ‘nekura-zoku’ (‘the gloomy tribe’), but none of these terms really hit the mark. For whatever reason, it seems like a single umbrella term that covers these people, or the general phenomenon, hasn’t been formally established. So we’ve decided to designate them as the ‘otaku’, and that’s what we’ll be calling them from now on.”

(The translations here are Matt Alt’s, and you can read the full essay here. The original Japanese is available here.)

You don’t need to get his cultural references to recognise these playground stereotypes: Nakamori’s definition of otaku plays on the universal childish desire for acceptance; the need to blend in. Otaku are those who don’t and can’t conform: they’re uncool, they’re unpopular, they’re weird, ugly and outcast. In short, otaku are everything the “normal” person ought to revile.

The real origins of otaku

Nakamori may have been the first to define otaku, but he was most certainly not the originator of the term.

In Japanese, the term otaku is an honorific second-person pronoun – basically an extra-polite, formal version of “you”. When Nakamori chose the term it was already commonly used by manga and anime fans to refer to one another – an atypical usage thought to have been inspired by the animators Shoji Kawamori and Haruhiko Mikimoto, who used it to refer to one another while at university. Toshio Okada, the anime producer, foremost otaku expert and reigning “OtaKing”, has explained that members from different fan clubs originally began using the term otaku to refer to one another as a mark of mutual respect (read more here).

Nakamori thus took the term chosen by otaku to describe themselves and co-opted it for his own purposes, turning it from a mark of respect into a mark of derision.

The Otaku Murderer

The negative connotations of otaku were cemented in 1989 when the serial killer Tsutomu Miyazaki was apprehended for the murder of several young girls.

Miyazaki was a social outcast (he was born with deformed hands, which led to his being ostracised by his peers), and had a large collection of anime, pornography, slasher and horror films. These were later seized on by the prosecution as an explanation of his divergent behaviour.

(On a side note, later critics of Miyazaki’s trial – including Eiji Otsuka and Fumiya Ichihashi – have claimed that the otaku connection was played up to take advantage of existing negative stereotypes against the subculture, and have even suggested that Miyazaki’s pornography collection may have been added to by a photographer in order to emphasize his perversity. Such accusations are certainly not beyond the realms of possibility.)

In any case, foul play or no, the media swiftly began calling Miyazaki “The Otaku Murderer”, and society at large duly flew into a panic about the perceived dangers of this reclusive, antisocial subsection of society. As The Verge has written, “the image of his room — unoccupied and windowless, with videotapes stacked to the ceiling around a small, rumpled bed — became the dominant impression of an entire subculture”. In other words, it was the final nail in the coffin for otaku PR.

Thus, by 1990, otaku was firmly established as a pejorative term – a byword for weirdness, social ineptitude, perversion, and detachment from reality.

How otaku became cool

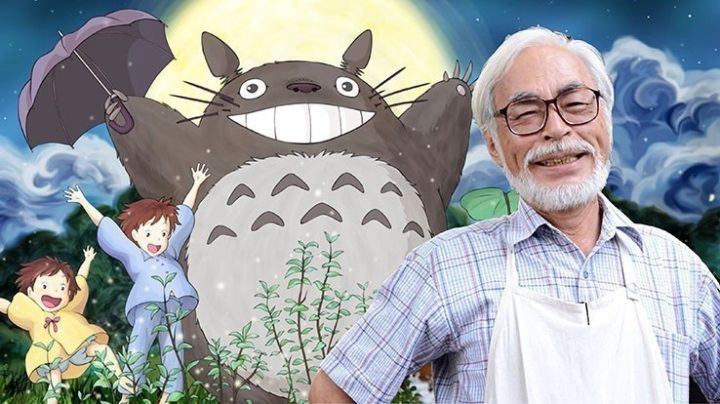

Fast forward to 2016 and the picture looks rather different. Beginning in the 80s and picking up speed in the 90s, Japanese pop culture exploded into the worldwide mainstream – and this explosion was driven by manga, anime, and gaming. Nintendo won a place in our hearts with vastly successful franchises such as Super Mario and the Legend of Zelda; Sanrio tapped the global market for kawaii with Hello Kitty; crazes for Power Rangers, Transformers and tamagotchi captivated playgrounds, anime cartoons like Sailor Moon and DragonBall Z enraptured young audiences across the world, and the phenomenon of Pokémon swept through the world like a plague of cute, yellow, electrified mice. Then, when the anime masterpiece Spirited Away by Hayao Miyazaki (definitely not to be confused with Tsutomu Miyazaki) won Best Animated Feature at the Oscars in 2003, anime came to the attention of the adult population – and Studio Ghibli was suddenly a household name. Japanese animation was officially cool.

(The rise and rise of Japanese pop culture is something I’ll investigate in a future post – but for now you can read more here).

But while Western audiences were blithely unaware of the negative connotations of otaku-dom, the stigma clung on more tenaciously in Japan. From Tsutomu Miyazaki’s conviction onwards, the otaku community made constant attempts to reclaim their term – beginning with The Book of Otaku, a collection of 19 essays by otaku insiders printed in the 104th edition of Bessatsu Takarajima magazine, published in 1989.

Negative attention has reignited over the years (during the trial of child murderer Kaoru Kobayashi in 2004, for instance – even though Kobayashi wasn’t an otaku) but as Hiroki Azuma notes in his 2009 book, Otaku, this has been tempered more and more by acceptance. Hayao Miyazaki’s Oscar was a watershed moment, as I have mentioned, and Azuma points to various other landmark signs of destigmatisation: the rising popularity of Takashi Murakami’s anime-esque artwork, for example, or former prime minister Taro Aso choosing to identify himself as an otaku.

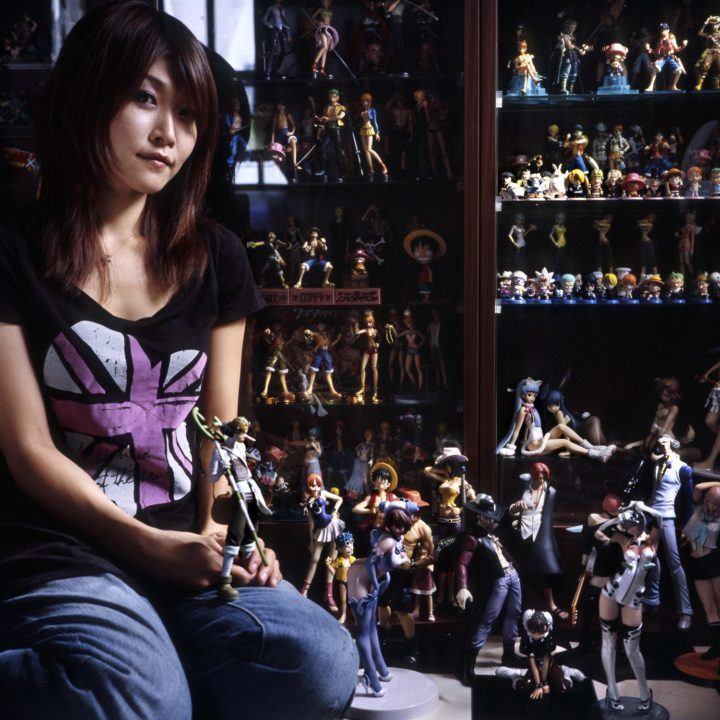

Nowadays there are many books, blogs and other outlets celebrating otaku culture, such as Patrick Galbraith’s Otaku Spaces, a book of intimate photographs and interviews with self-proclaimed otaku. Today’s otaku even have their own tribal homeland: the Akihabara area of Tokyo. Little by little, the stereotype is being exploded.

Otaku culture is worth celebrating

Different = bad. It’s the age-old, narrow-minded logic of the bully. Critics of otaku attempt to secure their own definition of “normal” by denigrating the “weird” and their “perverted” interests – and in a society like Japan, where communality is traditionally prized and individualism censured, it’s no surprise that otaku have been hounded out of the proverbial village. (Speaking of which, Tsutomu Miyazaki was a social exile long before becoming a murderer – rejected by his classmates due to a physical deformity. I’ll wager that had more to do with his later behaviour than his penchant for comic books).

And it’s not just their paranoid tendency to bolster their own identity by disparaging others that we should take exception to – critics of otaku are also guilty of disregarding a crucial fact: that otaku culture itself is an incredibly rich and fertile ground for creativity.

For one thing, otaku are responsible for the growth of manga, a form that has been largely ignored in other cultures but which in Japan is a deep, complex and well-respected genre in its own right. They are also the brains behind Comiket: the world’s largest fair for dojinshi (self-published material), which commands an attendance in excess of half a million and offers amateur writers and artists an outlet to challenge the forms and ideas of mainstream media. It’s counterculture pure and simple, and if you give two figs about creative innovation you should find it incredibly exciting.

Throughout history, the world’s best and brightest have often been social pariahs – their views and lifestyles rejected by the general populace, forced into the fringes of society along with the mad and the criminal. The list of famous thinkers who were considered losers and crackpots in their lifetime is long.

So hooray for otaku, and long may they thrive! May they cease to be identified with the lunatic fridge and be embraced as the trailblazers they are. After all, nothing interesting ever came from following the herd.

Learn more about otaku culture on our J-Pop & Go! Small Group Tour, or look at our Manga & Anime Self-Guided Adventure for inspiration.