Like this post? Help us by sharing it!

Stephen Phelan is a journalist with close ties to Japan – he once lived in Kanazawa, and has volunteered in the tsunami-stricken Tohoku region various times. As the sixth anniversary of the disaster approaches, he revisits the town of Onagawa to catch up with some of the residents and see the recovery for himself.

My first visit to Onagawa was a few weeks after the tsunami of March 2011. It was, at the time, among the most badly damaged towns along the Tohoku coast, with more than 70% of homes and buildings destroyed, and almost 10% of the population listed as dead or missing. Surviving residents kept insisting that the town itself had not been washed away.

Even while the wreckage was still being cleared, with so many still shocked and grieving, they were already eager to make plans and begin rebuilding. The friends I made there, and the local volunteers I worked with, often said they wished I could have seen the town before the disaster. To hear them describe it, Onagawa had been the most beautiful place in the world, or at least in Japan – its main port and adjoining fishing villages strung in a loose chain around the Oshika peninsula, between thick-forested mountains and deep bays of such bright blue water that their home football team was named Cobaltore.

Most people accepted, of course, that the “new” Onagawa would not and could not be the same as the old. And today, the reconstruction is still far from complete, but the town is very much alive again, and very different to how it existed before the disaster. I’ve been back to Onagawa several times in the intervening five years, but my most recent visit was the first since the train line from Ishinomaki was reopened, allowing me to arrive at the town’s new railway station, designed by Pritzker Prize-winning architect Shigeru Ban.

The structure looks like something from a Studio Ghibli movie, a welcoming and even somehow friendly structure with a roof like a hat that follows the contours of the mountains behind. Across the street at the waterfront, a whole new commercial wharf has been built on raised land that stands over the former town centre.

Drawn up by Azuma Architects to resemble a slightly funkier modern version of a traditional wooden Japanese village, Onagawa Seapal Pier consists of various restaurants, a diving store, a gourmet coffee house and craft beer bar, a ceramic tile factory and a workshop where electric guitars are carved from local sugi (Japanese cedar) trees.

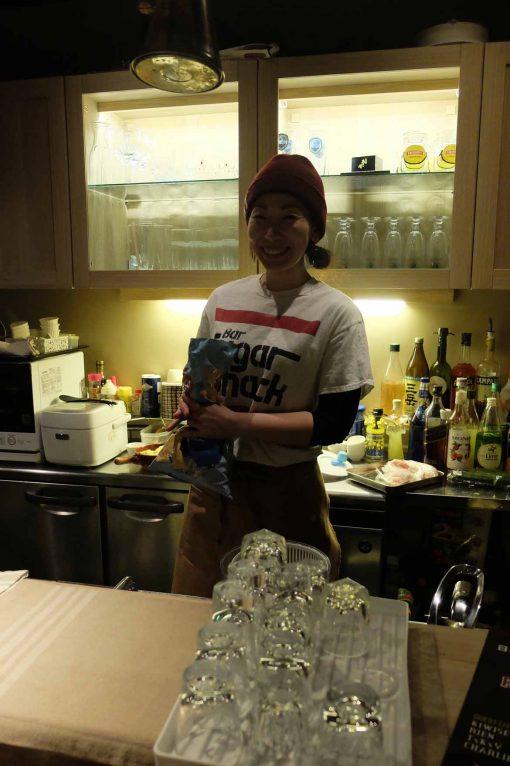

Next door from the latter is Bar Sugar Shack, a pub and club owned by Shuhei Sakimura, an Onagawa-born graffiti artist and hip-hop DJ who paints and performs under the name D-Bons. His wife Chouko Chiba helps him run the place. Chouko is from neighbouring Iwate Prefecture – which was also badly affected by the tsunami. She first came to this area in the aftermath, to volunteer with the Ishinomaki-based relief organisation It’s Not Just Mud (we worked together with that group in 2012).

Dropping in to say hi on a Friday evening, I passed a gang of teenage skateboarders doing slides, grinds, kickflips and other tricks I couldn’t even name on the concourse outside. They came all the way from Sendai, some two hours by train, because the long flat surfaces of the Seapal Pier are perfect for practice – especially after dark when the shops are closed and these new streets are quiet.

Inside the Sugar Shack itself, an Ishinomaki breakdance troupe called the Bi-Hive crew were performing headspins for an event that would also feature the famous Japanese rapper Rino Latina II, all the way from Tokyo. Nothing like this ever happened in Onagawa before the disaster, D-Bons told me from behind the bar.

When he was a kid, there was nothing to do at night but hang around outside the old train station. That world is gone now, washed away along with his house, his grandmother, his little brother. And if anything good is to come of all that loss, then D-Bons was inclined to think it should be a youth culture, a music scene, a sense of energy and vitality where there was no such thing before. His dream was that bigger hip-hop names would come from even further afield to perform at his bar – the ideal guest would be Nas, the superstar New York rapper who made his favourite record, Illmatic.

In the meantime, he spent his days painting murals on the storage containers used by fishermen in the main port and villages – covering them in brightly coloured animals and ideograms. He often used the word “kizuna” in his designs, which is difficult to translate but means something like “heart connection”. In the evenings he served drinks and spun records, with the able assistance of his new bride.

Chouko, for her part, had got to know Onagawa very well since we last met. She said the bar had become a hangout for a broad cross-section of the post-tsunami community. Regular customers included town officials and planners; health workers from the local hospital; young hip-hop fans from hereabouts, a 70-year-old widower who now came in almost every night to order Chouko’s spicy quesadillas; and sometimes the town mayor, who liked to break out his electric guitar and treat the clientele to some heavy rock riffs.

Mayor Yoshiaki Suda is a serious Iron Maiden fan in his early 40s – still a young man by the standards of Japanese bureaucracy, which tends to be the domain of grey-haired patriarchs. He used to be a member of Miyagi’s prefectural government but ran for office in his home town after losing his own house to the disaster, as well as several relatives.

Now Suda is given much of the credit for what Onagawa was lately become, a kind of model village for the reconstruction. Most of the Seapal Pier units are run by residents like D-Bons, many of whom have suffered similar losses. And by day, these shops and bars and restaurants are frequented not just by locals, but by visitors from all over Japan, who come to see the sights, pay their respects, and spend their money. Those impulses are fused into a form of capital – tourism is helping to fund the ongoing recovery.

National, prefectural and municipal budgets can only stretch so far, and this town in particular has become a hub for enterprise and entrepreneurship. Under mayor Suda’s leadership, the local business community has proven uniquely receptive to bright ideas and outside investors that might help Onagawa remake itself as a place where young people want to live and work, and a destination that travellers want to visit.

Like many small rural and coastal Japanese towns, it had been suffering long-term decline for decades before the disaster, losing one-third of its population between 1980 and March 2011, as residents left to seek employment in the bigger cities. As Suda has since put it, the catastrophe of the tsunami – the sheer scale of the destruction – also created an opportunity to address or reverse that problem, and blueprint a more viable, sustainable future. The waterfront and new commercial centre form one part of the plan, built on the blank slate left by the wave. The residential sector is another.

Houses can’t simply be re-raised where they used to stand, especially in low-lying areas that were completely inundated by waves of up to 30 metres. So land is being cleared and terraced in the surrounding mountains to make room for public and private homes at higher, safer elevations. It’s a massive, complex earth-moving project that will take another few years yet. But it’s still possible to find peace and quiet in those mountains too.

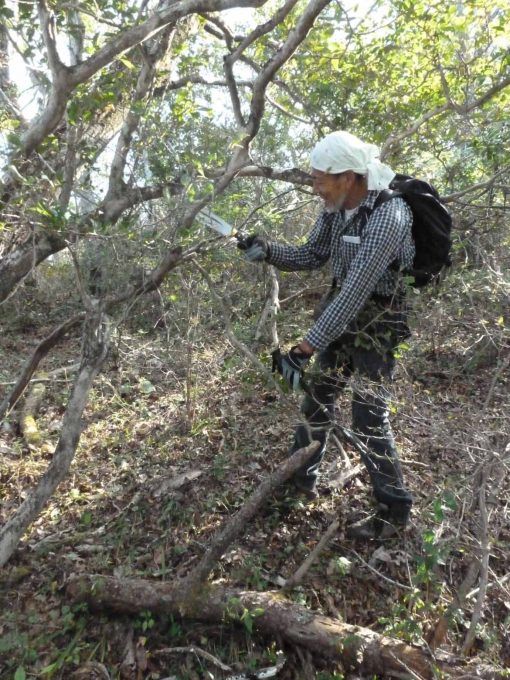

As a resource, they’ve been somewhat under-exploited, with trails known only to a few domestic hikers and climbers. The idea now is to open up these peaks and forests, make all this glorious scenery accessible to visitors from across Japan and the world. Local schoolteacher Ikuo Fujinaka has been commissioned to mark out routes for footpaths and nature trails, and he invited me to join him on one of his scouting missions.

We walked slowly up the side of Kuromoriyama, or Black Forest Mountain, to the highest summit overlooking the town. Fujinaka stopped every now and again to log our position with a GPS, taking notes and photos of flora, fauna and historic sites en route. He pointed out toxic plants that were once used to make poison arrows by the warriors of the Emishi people who once ruled this region. We passed Shinto shrines and Buddhist totems dedicated to the safety of the fishing boats that sail out of the harbour below.

There were marker stones dotted along the way to commemorate past tsunamis in this region – in 1896, 1933, and 1960. The last such disaster on a similar scale to March 2011 happened more than 1000 years before: the so-called “Joghan Event” of 869 A.D. It might be another millennium or more before the same thing happens again.

“But we have to remember, and we have to be ready,” said Fujinaka. The upper reaches of the path were overgrown, and we cut our way through with machetes so that it might be much easier for anyone who wanted to follow. When we got to the top, we could just about see through the trees, all the way down to the calm blue sea.

In the distance we could hear the earth-moving machines at work on the new Onagawa, and beyond that the weather and shipping announcements broadcast through the public-address system down at the port. “The fish are calling,” said an encouraging voice, which seemed like another way of saying: life goes on.

The Tohoku region is one of the most beautiful and underrated parts of Japan, and it needs tourism now more than ever. If you’re interested in paying a visit to northern Japan, take a look at our A Northern Soul group tour, which has departures in October and May.